A rocky spire glows in twilight. Colorado – June 2018 Velvia 50 4×5, 135mm lens 3 minutes at f22, no filters

If you’ve browsed through my images, chances are you’ve noticed that I’m a big fan of twilight and early morning light; the soft warm glow on the landscape is just sublime. Shooting in twilight comes with its own set of challenges, but those are greatly increased when trying to use a large format view camera. I’m going to share some tips that can help you out when the light is fading fast, or when you arrived well before sunrise and don’t want to miss the morning glow because you can’t see anything.

Use another viewfinder

Finding a composition on a large format camera is challenging in any light, you really can’t look through the camera until it’s on a tripod and there’s no better way to limit your compositions than by setting up a tripod before you have found the image. This problem is further compounded in the dim light of dawn as ground glasses are inherently dark. Take time to walk around and find the perfect spot – from the angle to the height – before you even think about setting up the tripod. This is best done by using something else as a viewfinder.

There are many things you can use as a viewfinder, from a primitive 4:5 rectangle cut out in a piece of cardboard to using a separate camera that has a viewfinder. The rectangle cut-out is an age-old trick and you can adjust the “focal length” by holding the window closer or further from your eye. My personal method is using a separate camera with a zoom lens that covers my entire lens range from 75mm to 210mm on 4×5. This camera is small (micro 4/3rds with a 12-50mm lens), has a similar aspect ratio to 4×5, and also doubles as my light meter. With the latest advancements in smartphones, these are also a great option and can preview an image in rather dim light. There are also a variety of apps that allow you to preview different focal lengths on your screen so you can have a rough idea of what it will look like with your different large format lenses. I’ve heard good things about Viewfinder Mark II for Apple products, and you might need to try a few different apps for Android.

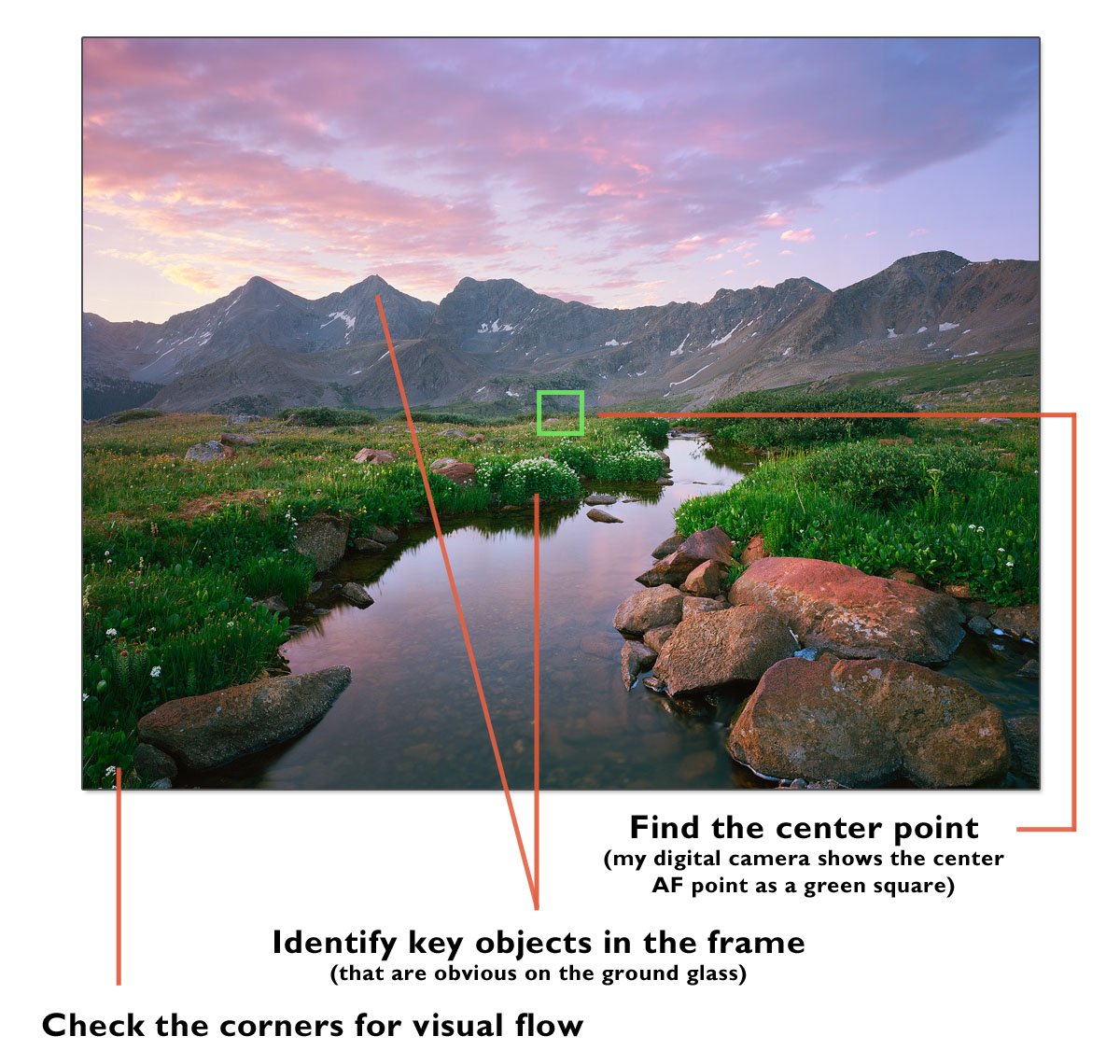

No matter what you decide to use as your dim-light viewfinder you can use them in the same way. In dim light it will be very hard to see fine details on the ground glass, but you can usually still see shapes unless it’s completely night time. Using your separate viewfinder, find the perfect angle, focal length, and camera height for your image and then set up your tripod and large format camera in that exact spot. Use some visual anchors that you saw in your viewfinder and compare them to what you can see in the dim of the ground glass. Good visual anchors are items such as a river that flows into a corner of your frame, or a tree that you know you want to be in one particular part of the frame. These are objects that are easy to see on the ground glass even in dim light. If you have chosen your focal length and camera placement correctly, then all you need is to have one anchor subject in the correct position and the rest of your composition will fall into place. On my “viewfinder” camera that I use it shows a little rectangle for the focus point in the dead center of an image after shooting and I frequently use this center spot as a reference for where the center of my ground glass grid should land. This center reference is all I need since I know the precise conversions for the focal length from my zoom lens to my large format lenses, but having an extra anchor object can make the composition more precise.

No matter what you decide to use as your dim-light viewfinder you can use them in the same way. In dim light it will be very hard to see fine details on the ground glass, but you can usually still see shapes unless it’s completely night time. Using your separate viewfinder, find the perfect angle, focal length, and camera height for your image and then set up your tripod and large format camera in that exact spot. Use some visual anchors that you saw in your viewfinder and compare them to what you can see in the dim of the ground glass. Good visual anchors are items such as a river that flows into a corner of your frame, or a tree that you know you want to be in one particular part of the frame. These are objects that are easy to see on the ground glass even in dim light. If you have chosen your focal length and camera placement correctly, then all you need is to have one anchor subject in the correct position and the rest of your composition will fall into place. On my “viewfinder” camera that I use it shows a little rectangle for the focus point in the dead center of an image after shooting and I frequently use this center spot as a reference for where the center of my ground glass grid should land. This center reference is all I need since I know the precise conversions for the focal length from my zoom lens to my large format lenses, but having an extra anchor object can make the composition more precise.

Use a Fresnel Lens

Fresnel lenses are an inexpensive option that can be added to just about any large format camera. A fresnel lens is a thin piece of plastic with tiny circular rings that brightens an image when viewed at a specific angle. These lenses usually work best with standard focal lengths (around 135mm to 210mm on 4×5) but will brighten up your view with any lens to some extent. The brightening effect is best seen when looking at the ground glass directly head-on and the image will dim significantly when you move your head to the sides. A trade-off is that you can sometimes see the rings when focusing with a loupe, but I personally find the benefits to outweigh the downsides.

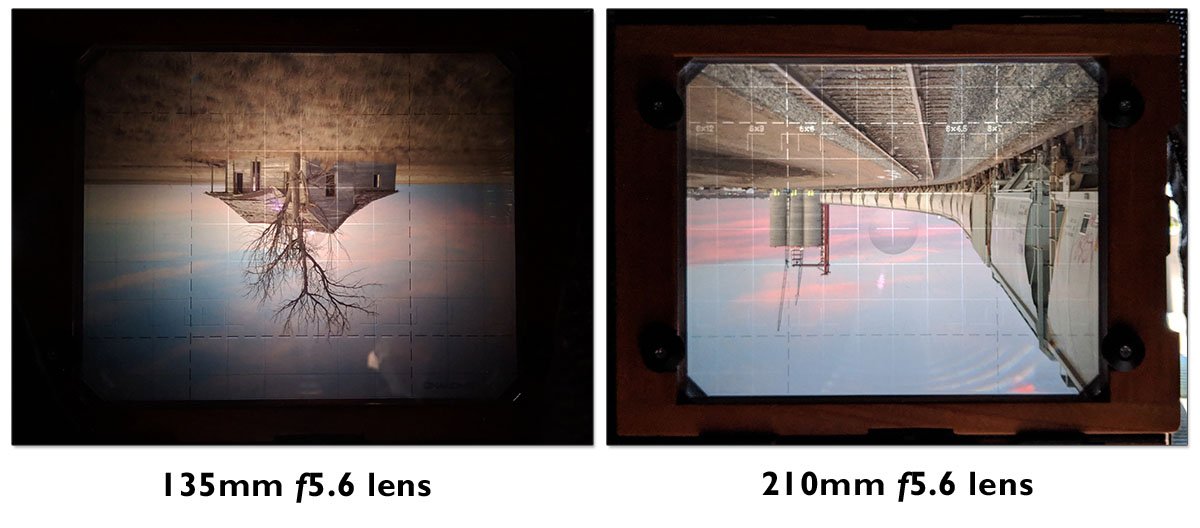

Ground glass views with 135mm and 210mm f5.6 lenses

Difference in ground glass brightness between 135mm and 210mm f5.6 lenses. Both lenses are shown wide open in light conditions that are nearly identical. As the lenses get even wider (such as 90mm) the view will get far dimmer on most fresnel-equipped ground glasses.

Your camera may already have a fresnel so you need to look into that before buying one; double-dipping won’t help you here. For years, I used the fresnel out of an old Crown Graphic on my Toyo camera and it worked great. I’ve also used a $40 Fresnel that you can get on eBay it’s also a good option, with much smaller and less visible rings than the old one I was using. A lot of 4×5 cameras use a standard sized fresnel lenses, but not all so you might need to buy one specific to your camera. Depending on the design of your camera, you may need to install the fresnel on the lens side or the user side of the ground glass. Either way is fine and won’t mess up your focus so long as you do not move the ground glass at all. The last part of that sentence is important.

Don’t go down the rabbit hole chasing the brightest ground glass on earth unless you have deep pockets. A lot of people think my ground glass is some magically bright screen, but on social media you’re only seeing the scenes where it composed brightly. So very often – especially when using wide lenses – the view is so dim that I can hardly see it, let alone photograph the ground glass view. Same goes with buying the brightest lenses with the biggest apertures; you’ll end up with a lot of heavy glass in your bag and a view that’s hardly any brighter, so you’re better off spending your time practicing some of these tips to compose in the dark.

Check focus with a loupe

Holding a loupe up to the ground glass really brings that small patch of the screen into brilliant detail when compared to the rest. After I have my rough focus set and a best guess at any tilt I might need applied, I pull out the loupe. Sunrise light happens quickly so try not to spend too much time here. Check your focus on a distant subject and a nearby subject and readjust your tilt or swing as needed. Movements in general can (and will) fill a whole blog post so I won’t go too deeply into them here.

Chances are in the dim of twilight that you’ll still be able to focus on your distant objects, such as mountains or a building. The contrast between the sky and objects will always allow you to focus on that fine line unless you’re working in the pure dark of a moonless night (when using a view camera becomes rather impossible anyway). If you’re having trouble focusing on your foreground then you can try using a very bright flashlight. The flashlight on your phone won’t do the trick here. I’ve used my hiking headlamp a handful of times, and some people have found some clamp-on lights to be useful on their tripods. Even in all the times I’ve shot in very dark twilight, It’s only been a few times that I’ve ever needed to illuminate the foreground to nail the focus. There’s almost always an object that will stand out enough from the rest of the foreground, such as the outline of water where it meets shore of a pond or a white rock in a field of grass.

The Teton Range reflects in calm waters. Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming – June 2017 Velvia 50 4×5, 90mm lens 8 seconds at f32, 2 stop soft GND filter

In order to be ready in time I had to set up and focus well before sunrise. I was easily able to focus on the peaks where they met the sky in the dark, as well as the foreground grass where it meets the water. Those objects have strong enough contrast so that focus can be nailed even in dim light.

GND filters

In true twilight there usually isn’t a huge brightness variation between the ground and sky, but I’ve found that a one-stop soft GND (Graduated Neutral Density) filter can really help with slide films like Velvia and Provia that are sensitive to even a one-stop overexposure. While it is always good practice to stop the lens down to your shooting aperture and carefully check the placement of the filter, I’m going to be honest with you and say that’s not always how it works. Sometimes it’s just too dark to really see the filter changing much on the ground glass – or when you stop it down to f22 or f32 you just can’t see anything on the glass at all. In this case, it’s ok to just guess the filter placement. Seriously, make your best guess based on where the sky and ground meet in your composition and place the filter that far down. If your sky is two-thirds of the frame, then place your filter with the dark line about two-thirds of the way down. This method also works with two-stop filters in a pinch, but I wouldn’t recommend guessing with a stronger filter than that. See more on GND filters here.

Twilight illuminated the southern end of the massive Rockwall towering above Floe Lake. Golden larch soak up the early morning light with vibrant colors. Kootenay National Park, British Columbia – September 2017 Velvia 50 4×5, 75mm lens 2 minutes at f22, 1 stop soft GND filter

Filter placement was almost impossible to verify in the dark so a best guess worked well here.

Get there early and act quickly

It’s going to take some extra time to work in predawn light, and you don’t want to miss the action by arriving too late. As sunrise progresses, you’ll find that there is a short window that occurs between the time where the light is too faint to work with film and the time that the predawn glow on the landscape starts to fade and the quality of light becomes harsh and less colorful. During this brief window of time – perhaps about five minutes long – you can see the sky take on warm purple/blue hues and a dark tone compared to the landscape which glows bright and warm in color. The light will be very soft and even which means you typically won’t need a GND filter at all in this magical light. I often find the exposures tend to be between one and four minutes long at f22 during this time frame on Provia 100f; since this magical moment doesn’t last all that long you need to be set up, focused, and ready.

In the evening this is much easier since you arrive while the light is still easy to work with and watch it fade into twilight. My main piece of advice for the evening twilight is to be patient. There can be a rather dull time a few minutes after sunset ends but before the twilight glow begins and it’s tempting to pack up your camera and leave. Hang out longer than you might think and wait until you start metering those exposures that are over a minute on Provia at f22 – chances are you’ll have some pleasant surprises from the light that you won’t notice with your eyes.

Twilight glow on a mysterious and colorful rock formation. Arizona – 2018 Provia 100f 4×5, 75mm lens 5 minutes at f22, warming filter

I was able to set up this composition while it was still light out, then waited until well past sunset. Be patient! The glow on these rocks was not impressive until it was surprisingly dark out, well past sunset.

Film Reciprocity

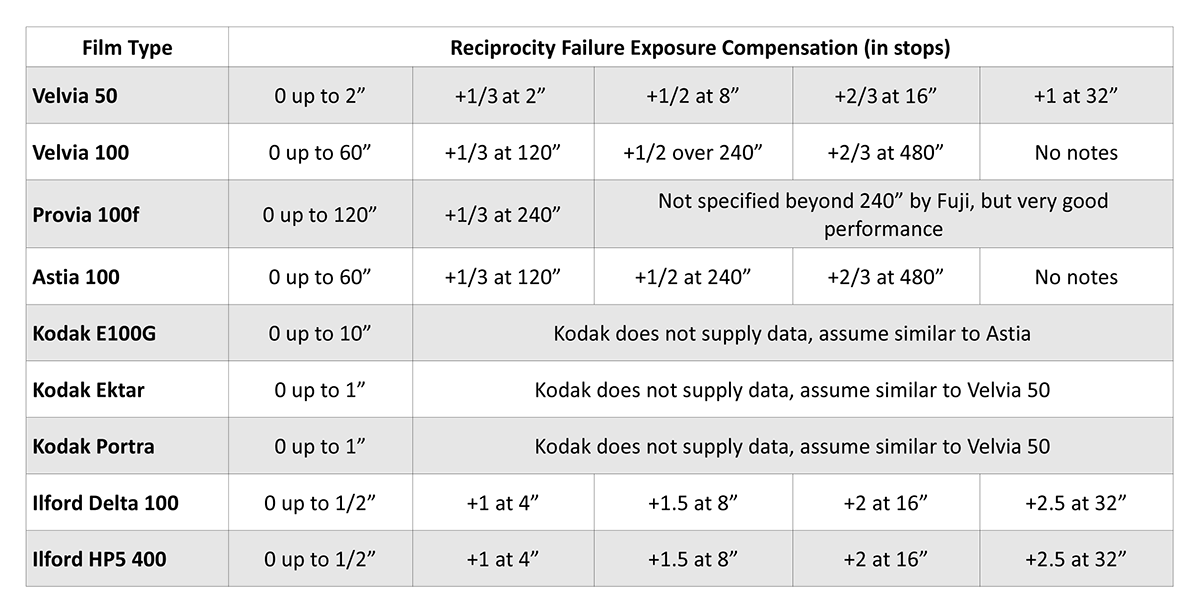

When working in dim light you need to be aware of the reciprocity characteristics of the film that you’re using. Some films such as Provia are outstanding for long exposures, needing no notable exposure compensation up to two minutes. Others like Velvia 50 are rather bad, requiring compensation starting at just 2 seconds. By the time your meter calls for a 30-second exposure on Velvia 50 you need to double your exposure and once you get into the minutes it’s a good idea to go even longer. Most color negative and b&w films (save for the now-gone Fuji Acros) also have poor reciprocity characteristics that are comparable to Velvia 50.

Reciprocity for common film types. Check the manufacturers’ data sheet for other film types.

Timing your exposures

Large format lenses only time themselves up to one second, which is nearly always insufficient for sunrise/sunset exposures. You’ll be needing to time the exposures yourself in B or T mode. With years of practice, I just count in my head for exposures up to a minute but pull out a timer on my phone for longer exposures. Remember that if you’re off by ten seconds on a one-minute exposure it will hardly make any difference as that only comes to 1/6th of a stop. I like to err on the side of going long when it comes to twilight exposures, especially as light is fading into the night after sunset. If you start a two-minute exposure in the evening, chances are by the time it’s over you’ll need two additional minutes as the light has faded further. It doesn’t hurt to recheck your meter reading during the long exposure and add extra time as needed. Same goes in the morning, you might need to shorten your exposure at the sunrise nears though this is something I worry much less about.

Rap The Film Holder!

This is always a good habit to get into before you insert the film holder into the camera. It took some messed-up film during a few long exposures to teach me this lesson and now I try to do it every time. It’s a simple step: just rap the film holder against your hand to settle the film firmly against the bottom edge of the holder. While the problem is less likely on slide film, on negatives such as Portra or Ektar that are physically thinner it’s possible for the film to “pop” into a different position during the exposure as temperature and moisture change from inside the film holder to inside the camera. The result is a weird double exposure that makes no sense – the edges of the film will be particularly affected while the center will appear less so. It’s worth getting into this habit to avoid the problem if you do long exposures often.

The Virgin River Narrows glow in reflected light over the cool flowing waters. Zion National Park, Utah – November 2017 Velvia 50 4×5, 210mm lens 2 minutes at f32, warming polarizer filter

A classic dark scene that makes large format a challenge. For this image, I used the corners to compose the scene and found a crack on the far well-lit wall to place the center of the image.

Hopefully, these tips will help you feel more confident when shooting in the dim of twilight. It really is some of the best light out there, and even better when captured on large format film.

If you found this blog post helpful, consider checking out my ebook “Film in a Digital Age.” Its 180 pages packed with knowledge and dive deep into all sorts of topics to help you master your film technique.

Thanks for reading!

Name – Alex Burke

Location – Colorado

Description: I’m a large format landscape photographer from Greeley, Colorado. Working with a 4×5″ view camera, I photograph the majestic beauty of the off-the-beaten-path wilderness areas as well as the subtleties of the Great Plains. At home in places far and remote, the best images are created by taking the time to really get to know a place and growing a deeper connection with the landscape.

Gallery: Alex Burke

Website: http://www.alexburkephoto.com/

0 Comments