Q: Can you tell me a little about your education, childhood passions, early exposure to photography etc.?

A: As a kid I always loved to spend as much time as possible outdoors, and landscape photography is a fantastic excuse for continuing that. My interest in photography though was sparked by a cousin who had pioneered a new approach to simulating architecture photographs. He used modified endoscopes which had originally been designed for medical purposes for photographing architectural models, simulating the pedestrian´s view of buildings not existing yet. This all was done long before computer simulations came up, and back then revolutionized urban development because for the first time it was possible to view planned buildings in form of models not just from a bird´s eye view, but from street level. But in the end it was a book from the Time Life series on photography in my father´s library which became life-changing for me. In that book there were two Eliot Porter images taken down in Glen Canyon before its tragic flooding which just struck me like lightning. Never had I seen before such a beauty in a photograph, and I immediately knew that I just had to visit that land of the canyons myself – and bring a camera. From there it still took me many years until my first expedition to the Desert Southwest, and even longer until I started to fancy large format photography. In the meantime I studied natural sciences, and at a glance one might think that a scientific perspective distracts from an artistic point of view. To my own surprise I realized that the contrary is the case: with a background in life sciences you inevitably have a different view on the natural world surrounding us, and this opens one´s eyes for structures and phenomena which one otherwise might have overlooked. Actually it turned out that this perspective is a steady source of inspiration, and it´s a perfect complement to a perspective primarily driven by aesthetics.

Q: Is that the “Approach of the Painter and the Scientist” you´re alluding to in your Artist´s Statement? Could you explain this approach in a little more detail?

A: Exactly, that´s how I called this confluence of scientific and artistic perception. The starting point here is the existence of two very different and ostensibly incompatible ways to perceive nature, represented by the perspectives of the painter and the scientist, and which in Robert Pirsig´s words one could call the “romantic” versus the “classic” perspective. The landscape painter is interested in a scenery as a whole, while the scientist will rather have a close look at the details, in order to understand what´s going on under the surface. For example, when seeing a dune, the painter will perceive its harmoniously curved, female forms and the play of light and shadow when the sun is low on the horizon. Were someone to hand him a camera, he would shoot images that capture the beauty, power or evanescence of what is seen. In contrast, the scientist’s interest is focused much more upon detail. He is preoccupied with causality, determinism, and natural forces and their interaction with one another. In seeking to explain why things are the way they are, he strives to trace natural phenomena back to the laws governing them. When investigating the same dune, he would examine a single grain of sand and would attribute the dune’s form, the angle of its slope, and the continual changes in shape caused by the wind to the physical properties of the grain. Through a camera lens he would concentrate on structures, patterns, and surface qualities by taking close-up shots, which would then in turn bear witness to the play of natural forces and their formative effect on animate and inanimate nature. By doing this, the researcher would render the reasons for the surface texture of the natural world visible. What fascinates me is the possibility to combine both perspectives in a single image, and to create photographs that evince two very distinct, and yet inseparably interwoven, levels: an aesthetic level (the effect of nature on the viewer) and a purely analytic level (the effect of formative forces on nature). As these levels are often located on very different scales of magnitude, an extremely high optical resolution is required for the fusion of both in one picture, and that´s where large format photography comes into play: the unequaled resolution of large format film allows to simultaneously record an almost infinite number of tiny details within a scenery, while still grasping the whole picture. Thus, a sufficiently large print – I prefer a final enlargement format of 70 x 100 cm / 30 x 40˝ at the least – allows the viewer to zoom in and out again and to switch between beholding the entire composition and viewing some of its countless details. This way, probably in most cases without realizing it, viewers switch back and forth between the perspective of the painter and the perspective of the scientist. I´m observing this frequently on the occasion of my exhibitions, and it´s interesting to see that people who hadn´t been in touch with the concept behind my images nevertheless follow exactly the path I had taken before upon creating the photographs.

Q: In most photographers´ lives there are ‘epiphanic’ moments where things become clear, or new directions are formed. What were your two main moments and how did they change your photography?

A: Yes, there are such moments, and in my case there actually were three which really changed a lot for me. I mentioned one already – my first encounter with Eliot Porter´s photographs of Glen Canyon. The other two relate more to technical qualities, one of them being the moment when I saw the first print made from a large format photograph. This happened to be a landscape photo, printed to Cibachrome material and hanging perfectly lit in a gallery. Before that I had seen countless large format photos printed in magazines already, and they always had some sort of difficult-to-describe appeal photos made with small cameras were lacking, but that print was just amazing. Having had fancied large format photography for quite a while, this was the moment when I decided to go for it and give it a try. The other moment was when I saw my first Diasec print on an art fair – must have been the Art Cologne I think. The brilliance and perfection of that print was so far beyond anything I had seen before that I simply couldn´t believe it. Back then I had been looking for a while for a way to present my images such that they would provide an immersive experience to the beholder, and I immediately realized that facemounting would be it.

Q: What are you most proud of in photography?

A: This question fits well to what you asked before, since the achievement I´m probably most proud of is my contribution to the development of the “UltraSec M” technology, or the face mounting of prints to anti-reflective glass. I mentioned my spontaneous fascination with Diasec, and for a while I couldn´t imagine anything of higher quality than prints face mounted to acrylic. However, I realized soon that the Diasec technology has two limitations: first, acrylic is extremely sensitive to scratches. Just wipe some dust off (which Diasec prints happily attract due to acrylic´s electrostatic properties), and you already introduced a host of micro scratches you´ll never get rid of again. Second, the reflections on acrylic are highly distracting, which is almost always a nuisance except under perfect lighting conditions. You may have such conditions in a gallery or a well-made exhibition, but almost nowhere else. Hang a Diasec print opposite to a window, and you´ll have difficulties to see anything but just a bright reflecting square on the wall. Using frosted acrylic was no alternative though, since the frosting takes away from a face mounted print all the brilliance which makes Diasec so special. I then realized that the ideal material for face mounting would be anti-reflective mineral glass used for architectural purposes (the very thin anti-reflective glass used for premium-quality framing would be too thin for providing the sense of depth face mounting is aiming at). The only problem was that apparently this wasn´t offered by any lab worldwide. So I decided to push the lab which I was working with to give it a try. They were not convinced, and in the end it took me two years of regularly following up on this until they realized that their only chance to re-gain their peace would be to just follow my request. And then the – for them – unexpected happened: the result of their first experiments blew our mind – no-one of us had ever seen such a brilliance, depth, three-dimensionality and vibrancy in a print like there right in front of us. All skepticism was blown away, and they instantaneously started a project to develop a routine manufacturing process of what became known later as “UltraSec M” prints. This was an extremely exciting time – I remember countless discussions of all the technical hurdles which needed to be overcome, but we all were absolutely confident that in the end this project would become a success. It took about two more years to optimize all those tiny little steps and tricks needed to manufacture immaculate prints at an acceptably low scrap rate, but I believe that what was achieved by the lab´s staff during this time was nothing short of the creation of a new gold standard for print quality. Since then I never looked back, and all of my exhibition prints and most prints sold to my customers are made using this technology. It´s also great to see that well-known artists such as Michael Wesely, Tom Fecht or Bernhard Edmaier quickly adopted this technology for presenting their awesome work.

Q: Talking about exhibitions – you´ve been quite active exhibiting your work, and had exhibitions among others on Photokina, in a museum, and on numerous festivals. Tell me about the experience of publicly displaying your work.

A: A well-made exhibition is just a wonderful way of getting in touch with people who are interested in your work, and at the same time it allows to create an immersive experience to visitors which can´t be created by any other setup – not by a box of prints, not by a book, not by a website and certainly not by an appearance on social media. I had countless wonderful conversations with people whom I otherwise would never have met, and it´s very gratifying to experience how one´s own work seems to speak to others, reaching them in a way words couldn´t. Sometimes I observe some sort of silent dialogue going on between a visitor and a photograph. When I approach these people and ask them what they like about a particular image, most aren´t able to explain their experience. They just feel attracted in a way which escapes verbalization – quite fascinating! It must be said though that, in order to create an atmosphere in which this sort of magic can happen, some efforts are needed. Prints must be of the best possible quality, they must be large enough (my exhibition prints are between 85 x 120 cm / 34 x 48´´ and 100 x 280 cm / 40 x 110´´), they need to be well lit, and everything must be arranged such that the visitors really focus their attention on the prints and forget the environment. I believe that, for creating a really good exhibition, there is no way around shooting large format and printing big. I have seen countless exhibitions of excellent work as such, but made with small cameras, and most of the time I was disappointed. Either prints are no bigger than the size permitted by the red face test when printing 35 mm negatives or DSLR files (somewhere around 30 x 40 cm, maybe slightly larger when printing a 36+ megapixel file), and they just get lost in a somewhat larger room. Or they are at a size beyond the technical limits of the original (sometimes shamelessly far beyond that limits) – then they may look good from a distance, but become a disappointment when getting closer, leaving a sense of dishonesty to the viewer: I cannot help to feel betrayed when inspecting a print at close range, and all I then see is coloured squares instead of details. That aside – for setting up an exhibition in a room which is not equipped with gallery rails or the like I´m using a set of metal racks equipped with halogen spots, so I´m independent of any available infrastructure except a few plug sockets. This can look quite good, and has the additional advantage to allow for arranging the photographs in groups, away from the walls and responding to the show room´s particularities. But by far the most enjoyable exhibition I had so far was the one in the museum, where the curator took a full week to arrange the photographs and to fine-tune the illumination, turning the exhibition space into a room just filled with light and colors – a perfect dream!

Q: Where/how do you get your pictures printed?

A: I have a wonderful long standing collaboration with a small company which does all the lab work for me, including developing, printing and face mounting. They own a LightJet XL which allows printing up to a size of about 180 x 300 cm (72 x 120´´), in excellent quality. When they print a new image for the first time for me, I´ll be on-site and discuss the test prints with the owner, who has an admirable understanding of colours. I learned quite a lot from these discussions, including the fact that objective colour perception appears to be different from person to person. What I mean by this is that to a certain extent colour perception is not a matter of taste, but as I suspect rather has to do with individual differences in colour receptor density and/or receptor sensitivity in our eyes, resulting in something you could call an individual white balance – an important fact to keep in mind when making or having made prints not just for oneself, but for others.

Q: Could you tell us a little about the cameras and lenses you typically take on a trip and how they affect your photography.

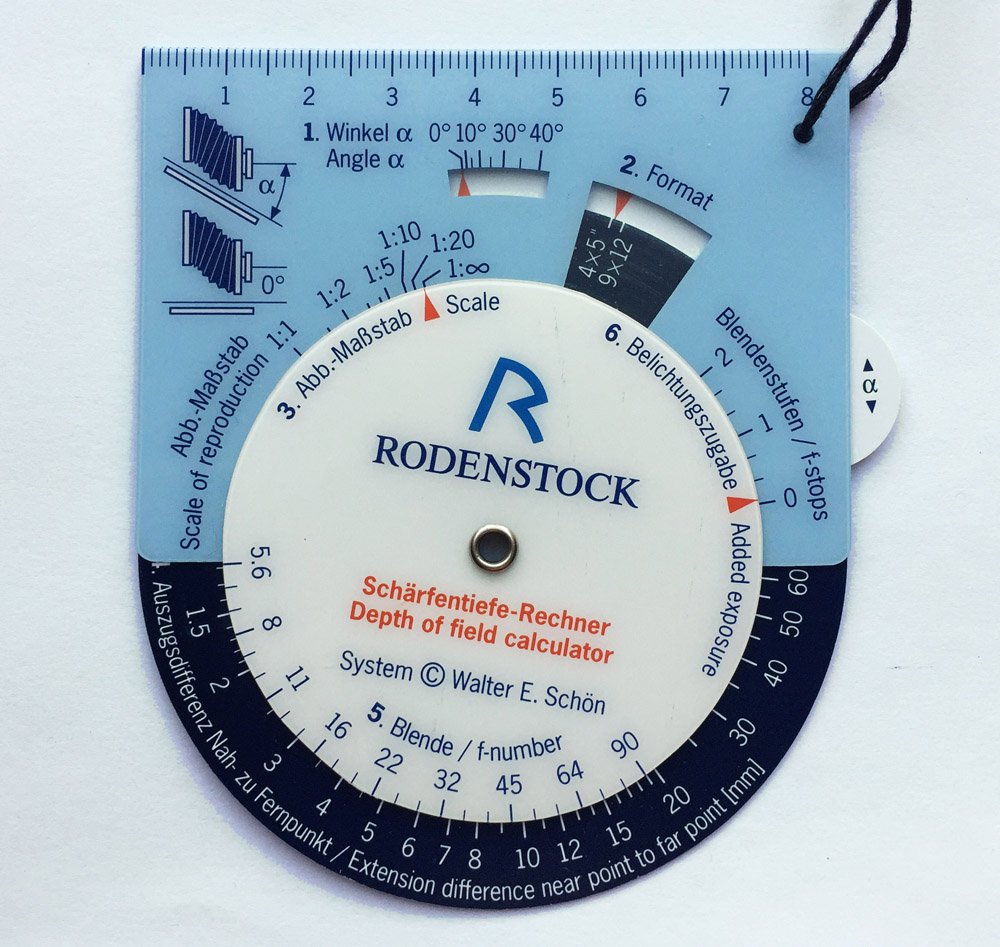

A: My main camera is a Sinar monorail camera, which most of the time I´m using with a 5×7´´back, in particular when air travel is involved and the 8×10´´back is too bulky. This Sinar has been modified such that I can also take panoramic shots in the format 5×13´´, which allows the production of murals in ultrahigh-resolution, several meters wide. I´m using lenses with a focal length of between 90 mm and 720 mm (35 mm / full-frame equivalent 20 mm to 170 mm), but more than two-thirds of my photographs are taken with my beloved 150 mm Schneider Super-Symmar HM, followed by a Fujinon-C 300 mm lens (corresponding to 35 mm and 70 mm full-frame lenses, respectively). I guess what I particularly like about these two lenses is that they allow such unexited perspectives – they don´t add any artificial drama to a scene and thus provide images with a very relaxed and natural look. As regards large format as such, specific equipment aside, this certainly tremendously affects a photographer´s style. The bulk, weight and slow speed of a large format camera, together with the costs (clicking the shutter once costs me around £10 / $12 for film and development), make you think more than twice on where, when and whether to go, how to compose your image, which light you are hoping for, and so forth. All the limitations I´ve mentioned render photography a much more conscious process, and that of course has an impact on the results you´ll bring home. Instead of taking two dozens of variations of a subject with your digital camera (and possibly missing the best one since you´re so busy with filling your memory card with all the variations you can think of), with a LF camera you´ll probably take just one photo, but this one has good chances to be your definite interpretation of that subject. Another but related aspect is how you are composing a photo when shooting large format, which is quite different from using smaller cameras. You see a two-dimensional image projected to the groundglass, similar to the finished print, without the illusion of three-dimensionality optical finders of small cameras are providing. This clearly facilitates that reduction from three to two dimensions which photography is all about. Then that image on the groundglass is turned upside down, which makes it easier to see an abstraction of one´s subject to shapes and colours. Finally, under the dark cloth you´re isolated from the outside world (except sometimes from biting insects, I have to admit), so you can fully focus on what you see on the groundglass. Taking this all together one has to say that all these factors which at a glance appear to be disadvantages of LF photography in practice turn to a strength, and simply lead to better results whenever speed is not a limiting factor.

Frank Sirona

Name: Frank Sirona

Location: Germany

Description: I´ve been interested in landscape photography since I saw for the first time a number of dye transfer prints made by the pioneer of color landscape photography, Eliot Porter. After my Nikon years I had a brief affair with a Mamiya 7, until in 2004 I finally upgraded to large format. Since then I´m shooting film using my swiss made 4×5, 5×7 and 8×10 Sinar cameras. Of these, the 5×7 has by far become my favorite, since weight and bulk of a 5×7 are still somehow manageable when air travelling (flying with a 8×10 monorail is a pain, believe me!), while the big groundglass is just a joy and makes composing easier than with a 4×5 camera. Also I personally do like the 5:7 side ratio much more than the 4:5 ratio of the other two standard large formats. The majority of my work has been done in the Desert Southwest, and I continue returning there whenever I can.

Website: https://www.franksirona.com

Instagram: @franksirona

0 Comments